balance (anbai) [Kō Mori]

Mori Akira Profile

Economist. Affiliated with a think tank (United States). Specialties are exchange rate policy, monetary policy, macroeconomic policy, and financial regulation. Interacts with market participants, financial authorities, and policy makers, and analyzes exchange rate movements from multiple perspectives.

Note: This article is a reprint and editorial revision of FX攻略.com August 2019 issue. Please note that the market information stated in the main text may differ from the current market.

Recently, a friend in California traveled to Tanzania. He sent many photos of lions, zebras, elephants, and more. Every photo shows professional-level skill. Admirable.

One of the landscapes that soothes in the United States is the squirrels seen here and there (image ①). Long ago on a college campus, in the shade of a tree on the lawn, while drinking a Coca-Cola and eating pizza for lunch, a squirrel gave me a greedy look, so I shared a piece of pizza with it. The squirrel happily carried the piece up the tree and devoured it with a satisfying munch. That sight brings a smile. Above all, the surprise was witnessing a squirrel eating pizza with my own eyes.

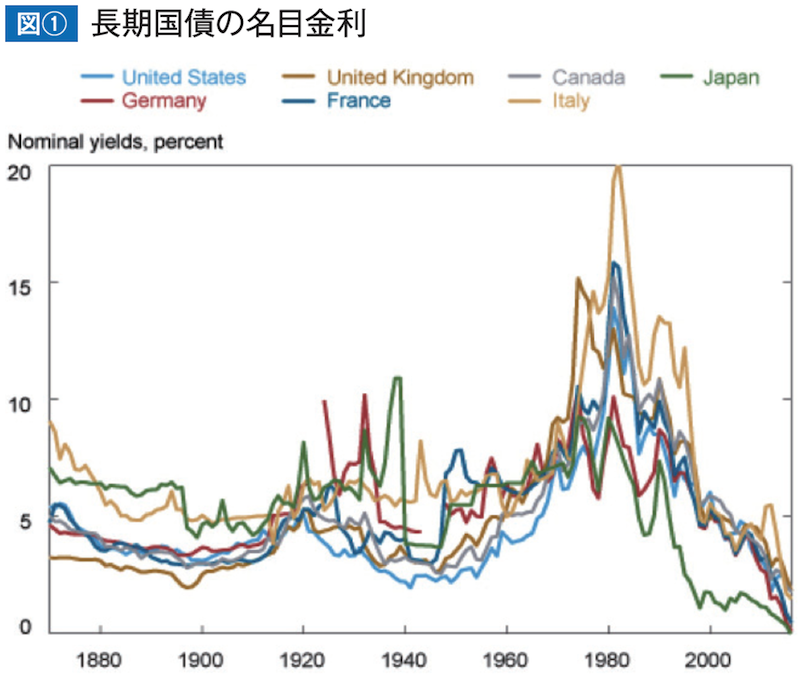

Interest rates on long-term sovereign bonds in advanced economies have been on a downward trend

I want to consider the long-term interest rates of advanced economies over the last 150 years.

Figure 1 shows the nominal interest rates on long-term government bonds for the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, Germany, France, and Italy. Since the 1980s, nominal long-term rates have been on a downward trend. The real interest rates of these long-term government bonds have also converged toward low rates over the past 40 years in a synchronized manner.

An economist who analyzed these low-rate trends concluded that the causes are: 1) robust demand from investors for highly liquid, safe assets; 2) global economic stagnation. I would like to discuss these findings further.

Indeed, before the Lehman Brothers crisis, the Federal Reserve (Fed) raised the federal funds rate, but long-term rates did not rise much. This was likely due to the strong demand from current account surplus countries for highly liquid, safe assets. Especially, excess savings from surplus countries such as Japan and China contributed to purchases of U.S. Treasuries, which are considered triple-A and highly liquid and safe assets. This massive purchase of U.S. Treasuries was not bad for the U.S. economy. However, major U.S. banks, due to these large purchases, found it difficult to maintain the spread between short-term and long-term debt, which led them to actively engage in buying subprime loans.

Why were banks able to actively promote buying subprime loans at that time? Because under the then-existing financial regulations, financial products that included subprime loans were still categorized as triple-A assets known as "super senior." And this securitized product responded to strong demand from investors as a new product.

Generally, subprime loans are described as creating a housing boom in the United States, with securitized products being issued to finance it. However, the true explanation is that there was a preexisting strong demand for securitized products in the market, which formed the base for subprime loan purchases.

Next, to consider the stagnation of the world economy. This magazine has touched on this theme several times, so I will keep the explanation simple. Notably, former Treasury Secretary (Harvard professor) Summers's "secular stagnation" theory argues that advanced economies and the global economy are experiencing a more serious shortfall of demand.